Articles |

|

||

|

• OBSERVATORIUM VOOR HET MENSELIJK GEDRAG • UNE MICROSOCIÉTÉ : LES TENTES DE DRE W • Touching Down in Public Space / english • Canvas Creations / english • The New Masters / english • A tent for all birds / english • Een tent voor alle vogels / dutch • Jumping the Boarding / english • Over De Schutting Springen / dutch • Stands and Tents / english • Lemniscaat / italian |

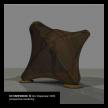

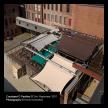

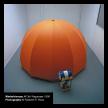

Stands and Tents / english Fieke Konijn in STANDS and TENTS, published on the occasion of the same exhibition in the Centre of Visual Arts Dordrecht, March 1999 Since his exhibition in Amsterdam in 1993, Dré Wapenaar has made ten tent sculptures. With the exception of the most recently completed work, all of these sculptures have already been on display at various locations, though in most cases separately. Now the CBK in Dordrecht has exhibited them together in a major exhibition for the first time, giving us the opportunity to reflect on the special qualities of his work. Wapenaar’s exhibition in Dordrecht will form part of a series of projects and presentations devoted to art in public spaces. In the course of history, the relationship between art and public spaces has taken all kinds of forms. A feature of the nineties has been that many artists object to taking a merely visual approach to enhancing public spaces. After all, even if they were involved in the design process from the outset, would this not limit their efforts to a cosmetic exercise? At the same time, public spaces exert a great attraction on artists who wish their work to function outside the context of the museum or other art institution. In many cases, they create work which does not primarily offer a visual experience. They are more interested in investigating the conditions in which art functions, for instance in public spaces, than in producing images or objects per se. A theme which has gained prominence within this tendency in recent years, and indeed one which has a more general cultural-historical relevance today, is the interaction between what is regarded as private and public. The artist’s concerns may extend to the tension or conflict between them, but also to the interpenetration and mutual influence between the two spheres. That may, for instance, lead him to enter and report back from the private worlds of individuals. On the other hand, his work may break taboos by laying bare intimate facets of his own environment. Wapenaar’s work fits within these developments, even if he is less interested in the contrast between public and private than in how the individual and the group relate to each other. With his tents, Wapenaar brings together people in a particular situation in order to see how they react. The form of the tent has proved a very productive one for him. It is an archetypal and universally recognisable form and one which connects with the essence of human existence. At the same time, the making of a tent, with its construction of frame and canvas, offers Wapenaar the sculptor ample scope to make his personal mark on that archetypal form. For Wapenaar, the visual aspect therefore does continue to play an important role. The first time Wapenaar used the tent motif was at the 1993 exhibition referred to previously. This sculpture is built up from the tilted forms of a family tent, a child’s tent and a windbreak. Wapenaar was inspired to make this work by his memories of family camping holidays. The idyllic image of a field full of tents, large ones for the parents surrounded by smaller tents for the children, is abstracted to create a colourful and playful spatial experience. This was not the first time Wapenaar had used prefabricated forms. In earlier works these were frequently elements with architectural references, such as doors, window frames or awnings. They were given an autonomous sculptural function, often being literally turned upside down. However, their independence of their original context began to bother him more and more. He started to look for ways of allowing the visitor to become actively involved in the sculptural form. The ideal opportunity presented itself at the Solitary visions, dynamic views exhibition in Park Wolfslaar near Breda. The Family Tent he designed for this exhibition displayed much more direct references to daily life. From the outside, the Family Tent looks deceptively like an ordinary tent. Once inside, you notice a subtle direction at work. The sleeping section consists of two compartments, each one containing a bed which invites you to lie down and stare out through the window above your head. It is a very intimate space, a cell within mother nature into which you can withdraw. However, your privacy is inevitably disturbed if a second visitor enters and occupies the other bed, because the partition is extremely thin. Wapenaar is fascinated by the question of what happens then. Do people try to make contact with each other or do they feel embarrassed and hastily leave the tent? The tent provoked a good deal of aggression in Breda, perhaps because of its ready-made character, and indeed was later completely destroyed at the East exhibition in Norwich. Since his Family Tent, Wapenaar has only made tents intended for actual use. The purposes for which he designs them are mundane: showering, drinking coffee, reading the paper, buying a bunch of flowers, drinking a beer. Those activities have been chosen with some care. Wapenaar wants us to experience that many of the actions we perform without thinking essentially amount to rituals of social intercourse. These tents could rightly be called social sculptures. During the summer of 1997, the Shower Tent was for a time on display at the De Trip outdoor swimming pool in Houten. This small tent is a marvel of ingenuity and offers all the comforts you need to step into your own private world for a lovely hot shower. It works anywhere, because it has its own water tank and geyser which stand beside the primary form as separate sculptural elements. The main form is tilted like a jet of water from a shower head. The act of showering itself takes place in a transparent plastic inner tent. Towel and clothes stay dry within the enveloping outer tent. The BBQ Tent was inaugurated on the same playing field, on one of those still summer evenings when the whole world seems to be barbecuing under identical canopies. Like the Shower Tent, the BBQ Tent is made to a highly functional design. A circular canopy with a diameter of nine metres protects the diners and the barbecue itself from the vagaries of the weather. An enormous bowl-shaped fireplace stands in the middle of the tent. Above it is the opening to let out the hot air and smoke, along with other features to prevent overpressure. But that isn’t the whole story. The curve of the canopy is exuberant and in its line slightly reminiscent of the fifties. It dips a little towards the centre, but the canopy is at its lowest at the circumference, forcing you to bow your head when entering or leaving the circle. In this way, the choice of joining the group or staying to one side becomes a much more conscious one. For those inside, the canopy masks the horizon and reinforces the feeling of belonging. With this design, Wapenaar propels the barbecue from the sphere of the uniform party tent to the level of the social ritual where its origins lie. Because what else is a barbecue than the communal devouring of the spoils of the hunt? The Tree Tents, of which three have been made to date, were inspired by the Road Alert Group in England. These activists chained themselves to trees which were due to be cut down in the hope of saving them. Wapenaar set himself the notional commission of designing a tent which would make their vigil among the branches more agreeable. He designed a tent in the form of a water drop, to be suspended high above the ground between two giant trees. There, individuals could comfortably hold out against the superior forces ranged against them for some time. What a fine picture it would make: tents hanging among the leaves and branches like green tears, a sign of mourning. In the absence of giant trees in the Netherlands, the tents hung among the trees of the De Hertshoorn campsite near Garderen in the summer of 1998, where they were intensively used. The Newspaper Kiosk has been deployed in the Rotterdam public library and in the atrium of The Hague’s city hall. It is precisely in such surroundings in which the piece comes into its own, standing like a communications satellite returned to earth from space, an airy defence against the surrounding hustle and bustle. Readers sit with their backs to each other on a circular wooden platform in the middle of the tent. This attitude allows them to immerse themselves in the newspapers placed on the counter in the outer circle. Passers-by only see their legs, which they can rest on a circular bar. In this tent, Wapenaar has opted for movement from the centre outwards, which strikes me as a good metaphor for communication. The reading does take place in temporary isolation, but the shared seat can nonetheless make it an occasion for contact between readers. Circles again play an important role in his three most recent tents, the Coffee Stand, Flower Kiosk and Beer Tent. Wapenaar uses this form repeatedly in order to influence the quality of the encounter. As such, we can detect a certain consistency in the intention behind these and previous tents. Given the archetypal associations of the circle, which are abundantly clear when we think of the history of architectural forms, this is perhaps only natural. However, in each situation, Wapenaar looks for an expressive form which characterises the essence of the activity and gives it a certain emotional charge. This is particularly striking in his 1996 Winterbivouac, in which the orange glow of the tentís canvas gives those seated around the stove the feeling of being back on mother’s lap. In the days when coffee drinking was a recent innovation in Europe, people would gather in special coffee houses. Now we drink our cup of coffee anywhere, in boring canteens, standing on a station platform, or wherever. The Coffeestand was created to study this behaviour. You can choose from three circles. The smallest has room for one person, another for two people and the largest for four. The coffee-coloured canopy further accentuates this layout. The design raises such questions as: who will choose to stand in which circle? Where will there be silence and where will animated conversations take place? The attendant has an excellent view of the proceedings and remains a detached observer because he stands in the centre of the field of force, where the three circles intersect. I think this exhibit will work with people behaving like gulls perched on ledge. They may be only slightly bothered if another gull joins them, but when the distance between them becomes critical they fly off. The Flower Kiosk again turns an established Dutch custom, in this case buying a bunch of flowers for your hostess, into an activity to be celebrated and consciously experienced. The flower seller rises above her wares like Flora, goddess of flowers and springtime, protected against rain and bright sunlight by a giant, dark blue umbrella lying on its edge. Around its tilted handle, a circular theatre is built up of flower containers, which can in this way be displayed temptingly one above the other. The same sense of temptation is central to the recently completed Beer Tent, a tent for quenching your thirst. The canopy consists of two spiral-shaped domes like enormous breasts, which float above the beer pump, operated by two women. These most recent tents take the theme of the loner versus the group into a new phase. More than before, they are designed to steer an individual’s interaction with other people. Once in the public arena, gender-related but also other patterns of expectation can begin to play a role. The same will be true for a number of tents which are still under preparation. Wapenaar is working on a tent in which a corpse can be laid out, and one which a VJ could use at work in a nightclub. Although Wapenaar's sculpture borders on design and architecture, he is not interested in a debate about the relations between the various fine art disciplines. He utilises function and manipulates space to seduce the viewer into participating in his sculptures. It is also not his intention to add disruptive or disturbing elements to public space. Wapenaar's sculptures should appear to belong wherever they are placed. As well as an enticing form, this demands a precise choice of location for the work, which is why he frequently turns down invitations to take part in art events. His intention to turn the viewer into a participant in his work should not be understood as a light- hearted attempt to involve more people in art. Wapenaar views participants as an element that can be utilised in the design of a work, along with material, colour and so on. However, participants introduce an unpredictable factor to the whole and their behaviour can bring surprises. Wapenaar highlights a single aspect of society, enlarges it, transforms it into a sculptural form and then puts it back. A situation then arises that leads the sculpture into all kinds of confrontations. The artist manipulates his pawns, but also has to bear in mind that these pawns may well run away with the game. Fieke Konijn amsterdam 1999 |